With all this money spent on marketing research, one would hope that it guarantees success for a company. It seems unlikely that a company would want to spend millions of dollars to better understand their target market, only to see unrealized gains. But there are still those that question whether or not there really are benefits.

Are marketing costs really worth it? This is an extremely difficult question to answer, especially because marketing is always seen as a cost center rather than a profit center. And from an outsider’s perspective, I can see how this is true. When a company says they spent $1 million in the last quarter on finding out how they can be innovative yet still meet the consumer’s needs, how does this translate to the bottom line? How is the marketing department supposed to prove to the upper echelon that the money the company spent so hard in earning was spent surveying the population? It seems impossible for marketers to turn around and tell management that for every dollar spent on marketing research, $x dollars was brought in as sales.

But from a marketer’s perspective, I can also see the flip-side to this argument. It seems silly for other divisions of a company to undervalue marketing. Without marketers, important insights would never be gathered for the company’s use. New product ideas, brand re-imaging, and product repositioning would be done without any support or reasoning behind the change. As a company without market research, you would be making assumptions about what the consumer really wanted. These assumptions are extremely dangerous and could greatly depreciate the bottom line of a company. With that said, not having marketing research kills the bottom line because it is very easy to make the wrong move.

Even if we were to argue that marketing research is a cost center, it still leads to the benefit for a company.

If we were to look at the value chain, we see that marketing is one of the last primary activities that lead to margins. With that link in the chain, companies create new products and techniques to better address consumer needs. By catering more to the consumer, the target end-user is more likely to purchase, which will directly drive sales. But if we remove marketing and marketing research, there is huge potential of driving the consumer away. We may think a new product innovation is what the consumer is looking for, but could actually be the exact opposite. This leads to unhappy consumers, which results in fewer purchases, lower sales numbers, and therefore a cut to the bottom line.

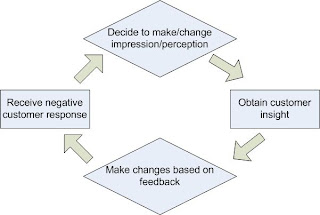

I think this issue of understanding the value of marketing and market research is especially interesting during the current economic climate. Everyone always says that marketing is the first thing to go when things are financially unstable and am appalled at this. It is imperative that companies continue to go out and research the population and gather, analyze, and make conclusions about the insights of buyers. It is imperative that we always stay on top of what they are saying and use their insights in making decisions about the direction of the company.

In finance class, we learn that the most important thing to a company is to maximize shareholder value. The way to do that is to add to the bottom line and return dividends to the owners of the company. And how do you do that? Sell your goods and services. The way to do that is to make sure that your goods and services really match what the consumer is looking for. And how do we do that?

Gain and understand customer insight.